A time of change: The evaluation of climate policy: theory and emerging practice in Europe

The European Union has just published the latest in a long line of reports which examine the progress achieved so far towards targets under the Kyoto Protocol as well as 2020 targets set at EU level. It reveals that collectively the EU-15 is on track to reduce its emissions by 8% from 1990 levels. But some states, notably Italy and, to a lesser extent, Spain, are unlikely to meet their domestic targets.

This latest report mainly utilizes country level emissions data voluntarily supplied by Member States. However, alongside this a new set of papers published by academic evaluators in Europe reveals that around, outside and beneath this formal evaluation activity coordinated by the European Environment Agency, more informal practices of climate policy evaluation are emerging.

A team of researchers from across Europe recently published a meta-analysis which offers the very first systematic cataloging of these emerging patterns of policy evaluation undertaken in different parts of the European Union. The study, which was published in the journal Policy Sciences and led by the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of East Anglia (UEA) and the VU University Amsterdam, was awarded the 2011 Harold D. Lasswell prize for the best article.

The study looked at six EU states studied - United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Finland, Portugal and Poland which broadly reflect the social, political and economic diversity of the EU. Given the obvious importance of EU-level action, evaluations were included that examine the operation of policies, such as the emissions trading scheme, that cover the EU as a whole.

The findings reveal that a culture of informal evaluation is slowly emerging: the number of evaluations produced has grown spectacularly in recent years. Data collected for six EU states and for the EU as a whole reveal an eightfold increase in the number of reports produced between 2000 and 2005. This growth, however, is more evident in some states than others. Policy effects in the UK, for example, are much more commonly evaluated than those in Portugal and Poland.

However, the culture of evaluation varies in other important ways. The majority of the 259 evaluations identified and studied also adopts a relatively narrow selection of evaluation tools and lack intensive stakeholder involvement. Crucially, over 80 per cent are uncritical i.e. they take existing policy goals as given. Finally, the majority are also quite narrowly framed, in focusing mainly on the environmental effectiveness and/or cost effectiveness of existing policies.

Whether climate governance is undertaken through the United Nations or "as now seems more likely" via more informal "pledge and review" type processes, evaluation practices are absolutely crucial for fine-tuning policy interventions and building and sustaining public trust. The most striking finding of the analysis is just how undeveloped and unsystematic are most current evaluation practices. Great efforts have been made to inform and understand policy making procedures in Europe, but most policy evaluation remains piecemeal and non-consultative.

As the political pressure on policy makers to describe and explain what is being done to tackle climate change increases, calls will grow for evaluation to be undertaken in a more open and transparent fashion. At present, policy systems in Europe seem ill-prepared to rise to that challenge.

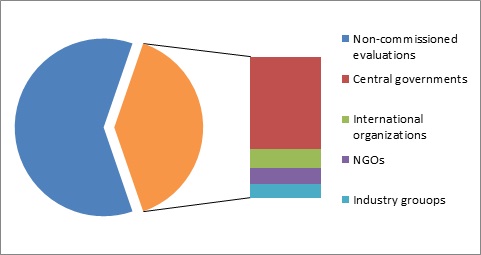

University researchers emerged as the most active policy evaluators in Europe. At present the majority of evaluations (58 per cent) are not commissioned. Of those evaluations that were commissioned, the most active commissioning agents were central governments (59 per cent), followed by international organizations (12 per cent), NGOs (10 per cent), and industry groups (9 per cent).

Percentage of non-commisioned and commissioned evaluations according to commissioning organizations

Policy makers could increase the total evaluation effort by commissioning more evaluations from a wider array of organisations. However, this may not necessarily produce a more active and questioning culture of evaluation. At present, non-commissioned evaluations are twice as likely to question policy goals as commissioned ones. By contrast, parliamentary bodies have produced a relatively large number of critical evaluations. The responsibility for enhancing the quality and the quantity of evaluations is therefore shared.

The evaluations studied date from the period January 1998 to March 2007. They were compiled from database and internet searches, supplemented by "snowballing" (asking different producers and users of evaluations for suggestions). All of them are effectively in the public domain.

The research was funded by the EU FP6 ADAM project, which UEA coordinated between 2006 and 2009.

Further reading:

The entire report, "The evaluation of climate policy: theory and emerging practice in Europe" by D Huitema, A Jordan, E Massey, T Rayner, H van Asselt, C Haug, R Hildingsson, S Monni and J Stripple

Some of the political implications of the findings have been explored in a related article: Haug, C. Rayner, T. and Jordan A. et al. (2010) Navigating the Dilemmas of Climate Policy in Europe: evidence from policy evaluation studies. Climatic Change, 101, 3-4 (August), 427-445.

Professor Jordan is an expert in EU and British environmental politics and policy making. He is an editor of the international journal, Environment and Planning C (Governance and Policy), and has also published more than 100 peer reviewed papers and chapters in edited books, he has also authored and/or edited 10 books. Professor Jordan also has experience leading EU funded projects including MATISSE and EPIGOV, and has worked with UK Government departments and agencies. He is an elected Academian of the Academy of Social Sciences (AcSS)